COP28 and its implications

A little over 30 years ago, more than 150 countries signed a UN treaty to limit the alarming rise of planet-warming pollution in the atmosphere. While the science behind human-caused climate change was still young, scientists knew even then it would be life-changing.

The first COP — the “Conference of the Parties” to that agreement — took place in Berlin in 1995. Member states have been convening on climate change almost every year since. In 2015, at COP21, more than 190 countries approved the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius, but preferably to 1.5 degrees.

Although the Paris Agreement was a landmark moment and set the world on a path that scientists supported, it didn’t get specific about how countries should achieve its goal. Since then, COPs have sought to make the plans attached to the Paris Agreement more ambitious and to be more specific about all the necessary changes society would need to make.

The controversy at COP28

The climate summit is hosted at a different location each year. While there have been other host countries mired in controversy, the backlash to this year’s host — the United Arab Emirates — has been particularly sharp; not only is the UAE a major oil-producing nation, it has also appointed a top fossil-fuel executive as its COP president. Critics say it’s a conflict of interest to have Sultan Al Jaber, the head of the UAE’s national oil company, taking charge of the most important climate conference of the year. In facing that criticism, the UAE has embarked on a major campaign to boost its green credentials ahead of the summit.

In May, more than 100 members of the US Congress and the European Parliament called for Al Jaber to step down, claiming that his role could undermine negotiations. Some key players — including US climate envoy John Kerry — have praised Al Jaber’s appointment. The UAE has rejected criticism that the country is unfit to host the world’s largest climate summit, with the COP28 team previously telling CNN that the UAE was the first in the Middle East to set 2030 and 2050 emissions reduction targets.

Heads of states and governments delivered speeches in the first days of the summit. More than 160 member nations, including the UK, France, Germany and Japan, were present. Perhaps the highest-profile attendee was King Charles III, who delivered an address at the summit’s opening ceremony. Absent from the speakers list was US President Joe Biden and China’s Xi Jinping — the leaders of the world’s top polluting countries. In mid-November, Biden and Xi pledged to significantly ramp up renewable energy in lieu of planet-cooking fossil fuels, and agreed to resume a working group on climate cooperation. In lieu of Biden, US Vice President Kamala Harris attended the summit – a trip that was announced following pushback that Biden was missing global meeting on an issue important to young voters.

Leaders from major oil-producing countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Syria, Russia and Iran, were among those attending. The UAE has also invited many fossil fuel executives to the climate talks, where they were expected to announce new commitments to decarbonize. A list of Wall Street financial heavyweights led by BlackRock CEO Larry Fink were also be present, after missing the summit in Egypt the previous year.

COP28’s global assessment

It’s been eight years since the Paris Agreement, yet the world has made barely any progress on slashing climate pollution, and the window is “rapidly narrowing” to do so, according to the agreement’s first scorecard — the global stocktake — which was published in September.

COP28 was the first time where countries entered negotiation rooms with an analysis that showed how seriously off-track, they are on their climate targets. Melanie Robinson, the global climate program director for the World Resources Institute, declared that the conference “told us clearly that the world is not on track to achieve our global climate goals, but it also offers a really interesting concrete blueprint and mountain of evidence on how we can get the job done, so it should be a wakeup call of what we need to do but with a roadmap to get there.”

COP28’s biggest issues

Some of the biggest concerns that took center stage in Dubai were continuations from COP27 in Egypt: finalizing a “loss and damage” fund and discussing how to ramp down planet-warming fossil fuels. A major debate among the parties has been whether to “phase out” or “phase down” fossil fuels. At COP27, a number of nations, including China and Saudi Arabia, blocked a key proposal to phase out all fossil fuels — including oil and gas — and not just coal. “The most important thing is the outcome at this COP sends a really strong signal that the world must rapidly shift away from fossil fuels,” Robinson said. “I would note that it’s important for the language to refer to all fossil fuels.”

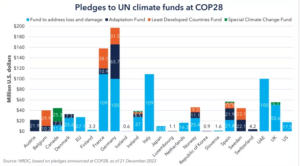

Another focus is on the so-called loss and damage fund, which countries included in last year’s agreement. The fund would help shuttle money from the richest countries, which are responsible for the vast majority of the climate crisis, to poor countries, where the impacts have hit hardest.

The goal is to get the fund up and running by 2024. With time running out, a special committee met in Abu Dhabi in early November and recommended the World Bank host the fund and serve as its trustee temporarily for four years. This loss and damage fund is a delicate and nuanced issue, said Nate Warszawski, a research associate with

WRI’s International Climate Action team. “I do think this could be one of the key issues that makes or breaks the COP”.

Another fund, the Green Climate Fund (GCF), is the world’s largest multilateral fund dedicated to helping developing countries address the climate crisis. Created in 2010, the Fund had its initial resource mobilization (IRM) in 2014 receiving $10.3 billion in pledges from 45 countries. The GCF underwent its first replenishment (GCF-1) in 2019, garnering a further $10 billion in pledges from 32 countries.

The GCF has a number of innovative design features, and is key to the grand bargain behind the Paris Agreement: that all countries need to do much more to tackle the climate crisis, but that the poorest countries, who did the least to cause the problem and are hit first and worst by its impacts, require support from the richest and highest polluting countries.

Marcello Tedeschi, Jan 22, 2024